Fat Shaming

…Calling out the bloated books

I have a special shelf in my wardrobe where I keep books that I’ve bought on a whim, but haven’t yet gotten around to reading. That shelf is currently groaning under the collective weight of these books, not because there are a lot of them as such, but because the books that remain unread are invariably the obese magnum opuses.

I have a special shelf in my wardrobe where I keep books that I’ve bought on a whim, but haven’t yet gotten around to reading. That shelf is currently groaning under the collective weight of these books, not because there are a lot of them as such, but because the books that remain unread are invariably the obese magnum opuses.

While my clothes are crammed into ever more crowded nooks, these elephantine literary tomes sit there like upholstered bulkheads taking up valuable storage space.

I realise that fat shaming is a PC no no these days, right up there with mocking vegans and forcing trans people to use the public facility of their gender of origin, but as books are inanimate objects – yes, even the best ones – hopefully I’m not guilty of transgressing this social nicety.

It’s not as if I’m no longer reading. Sure I don’t read with quite the same avidity that I once did, but I still get through a book or so each fortnight. In fact I’ve just finished a marvellous little slip of a thing called Grief is the Thing With Feathers by Max Porter. It comes in at a mere 114 pages, and that includes a lot of blank chapter dividers and post-modern pages with just a few words on them. Perfect. Before that I read Autumn by Ali Smith, which although 260 pages long, also featured lots of chapter gaps and was printed in the sort of oversized font normally reserved for the vision impaired.

The problem I’m encountering is that of the authors I habitually read (or at least buy), an unusually large number of them have suddenly turned into wordy windbags, publishing books that exceed what I, or anyone else with a life to be getting on with, would consider to be a reasonable word count.

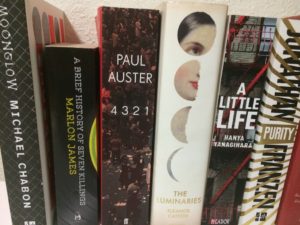

Sitting unread on my shelf in trade editions since their original publication dates are Jonathan Franzen’s Purity (563pp), Jonathan Safran Foer’s Here I Am (592pp) and Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (720pp) – a little life perhaps, but a fucking gigantic book. Even Paul Auster, who you can normally rely on to get bored with his own prose after page 200 has published 4 3 2 1 that comes in at a hefty 861 pages. Plus there are the recent Man Booker prize winners, Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings (688pp) and Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries (832pp), the latter of which has been resident on the shelf now for three years. It has almost acquired squatters rights. In fact a squatter could hollow out the pages and move in between the covers. Michael Chabon’s new book Moonglow is the most reasonable volume on the shelf, checking in at a comparatively wafer thin 430 pages.

“…it’s the sheer heft of these bloated, overweight tomes that defeats me”

There was a time in my life when unread books mocked me until the shame I felt at not having read them drove me to delve into their pages. The bigger and more worthy the book, the greater the shame and the more likely I was to peruse its prologue. In such circumstances did I get through many of the corpulent classics of the canon: Don Quixote (1056pp), Bleak House (992pp), Les Miserables (1232pp), Ulysses (768pp), The Brothers Karamazov (845pp), Middlemarch (864pp), Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities (1263pp) and Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past (3299pp) – by far the biggest of them all, and and on the action versus pages matrix, certainly the one with the biggest discrepancy. Plus of course the gold standard of fat mother-fuckers, even if it isn’t actually the longest, Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1261pp).

I’ve also read most of their modern equivalents: DeLillo’s Underworld (827pp), Murakami’s IQ84 (925pp), Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch (771pp), Harold Brodkey’s The Runaway Soul (835pp), Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day and Mason & Dixon (1085pp & 770pp respectively), Hilary Martel’s Wolf Hall (650pp), Tom Wolfe’s various 500+ page tomes and Vikram Seth’s behemoth, A Suitable Wife (1349pp). Doorstops such as Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (547pp), Gunter Grass’ The Tin Drum (589pp) and Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex (529pp), barely seem worth mentioning by comparison. And I won’t even detail the individual books by the Australians; Patrick White, Peter Carey, Frank Moorhouse and Eliot Pearlman, who it is fair to say all prefer the longer form.

This inventory doesn’t even include non-fiction. Seeking to justify the point of their endeavour, biographers feel obliged to string out the lives of their subjects to hundreds and hundreds of pages packed with dense, small font type plus footnotes and an index. I blame James Boswell and his ludicrously long Life of Johnson (1784pp) – readers of that fat fable are just thankful that dental care was in its infancy at the time and they were spared fulsome descriptions of the great man’s attempts at flossing.

Ever since then biographers seem to think they are unfairly reducing the significance of their subject if the finished work comes in at less that 600 pages. David Marr’s Patrick White (652pp), Hermione Lee’s Virginia Woolf (772pp), David Bellos’ Georges Perec (750pp), James Knowlson’s Beckett (704pp), Robert Ellman’s Joyce & Wilde (744pp & 554pp respectively), Rushdie’s memoir, Joseph Anton (633pp) and Don Watson’s book on Keating, Recollections of a Bleeding Heart, that came in at 734 pages and left the reader with the impression that it was actually Watson who had been the 24th Prime Minister of Australia, rather than Keating. Certainly he takes full responsibility for all of Keating’s triumphs.

I’ve consumed all of these massive masterpieces, lugging chunky Penguin paperbacks about on trams and trains, or propping bloated hardbacks up against my bedhead because they were too heavy to actually hold for any length of time.

I look at the their slab-like spines in my bookcase now and wonder where I found time, let alone the energy and impetus to tackle such monsters. Was I trying to impress a girl with the magnitude of my intellect? Make-up for shortcomings in my formal education? Compensate for my lack of hair or height or did I think a big book signified another oversized appendage? Whatever high-minded or low-principled motivation might once have guided me, it has now long dissipated. The simple truth is that I can’t be fucked reading fat books.

“…I needed daily physiotherapy sessions while reading a hardback edition of Roberto Bolano’s 2666”

It’s not that I don’t have patience with long-winded tales, although like everyone in the Twitter generation, I become a little restless once we cross over 140 characters. However, just as most TV series retain little semblance of plausibility after season two, it is a rare movie that warrants a running time of more than 100 minutes, and there are very few books that get better after page 400. Even Remembrance of Things Past began to grow wearisome after the first couple of thousand pages.

No, it’s the sheer heft of these bloated, overweight tomes that defeats me. If I wanted to lift 10 kgs at a time, I’d join a gym and do weights. I do most of my reading on the tram or train to and from work, so whatever book I’m reading I have to lug around with me all day. I needed daily physiotherapy sessions while reading a hardback edition of Roberto Bolano’s 2666 (898pp) and a shoulder reconstruction after attempting David Foster-Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1104pp).

It’s okay for the writers, they’ve got nothing better to do than write, but those of us with full-time jobs or family responsibilities can find it difficult to eke out the time – you look a bit pompous and possibly a little suspicious resting Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings (709pp) on your steering wheel while you watch junior footy training. And never take Nabakov to a netball match.

Why don’t I read on a Kindle, you ask. Well they have their place, but they’re not always the answer. My copies of Franzen’s Purity and Yanagihara’s A Little Life are signed copies, so that’s not something you can get on a Kindle. James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings has a list of characters at the beginning that requires repeated reference, Catton’s The Luminaries is a cyclical tale that also requires some back tracking, as does Auster’s 4 3 2 1 – a process that is not well-suited to to the Kindle. Kindles do not lend themselves easily to a quick skim – I’ve spent the entire journey home trying to re-find my place after quickly swiping back to some earlier reference near the beginning.

It is true that fat books represent far better value for money from a dollar per page perspective than a slim volume. For example, a paperback of Foster-Wallace’s Infinite Jest costs $27.99 for 1104 pages, or 2.5 cents per page, whereas Grief is the Thing With Feathers cost $14.99 for 114 pages, or 13 cents a page – and as I said, some of those pages are blank. And the word per dollar ratio only gets worse when you order a slim late era Beckett novella from overseas. So for the economically minded, fat books make more sense. But of course this only represents a saving if you actually read the books. My unread books I fear are destined to lay lifeless on my shelf like beached whales on the shore.

Theatre directors routinely edit Shakespeare plays to remove long-winded or irrelevant passages, and the Director’s Cut is no longer indulged in cinema. Even sports such as cricket, baseball, basketball and rugby continue to experiment with abbreviated forms. So as all other forms of entertainment continue to contract and truncate, it is perhaps time that publishers stopped indulging these wordsmiths from appending their overblown opuses and rediscovered the beauty and brevity of the abridged version.

As my own girth expands, my wife is placing the blame squarely on the hot chips and stubbies of Peroni that I habitually consume. However, I haven’t ruled out some complicated psychosomatic displacement in which the cumulative calories contained in all those fatty, flabby leaf books have somehow been transferred into my digestive system. I used to resemble a svelte Cheever novella, Oh What a Paradise it Seems (90pp), whereas now I’m more like the Collected Stories (896pp).

I shall end this here, for fear that this article turns into the very thing it rails against, but I do wonder if instead of author surname and genre, bookshops shouldn’t classify books from thin to thick. It would certainly make my choices easier.

Leave a Reply